A long lush memory is embedded

in the windswept plains, on the mesa tops and in the secluded mountain canyons

of northeast New Mexico. The land has kept a careful record of tracks and trails

to present a multi-generational morality play, the ultimate American Western.

Northeast New Mexico is a history lesson of what happens when two empires meet.

The older north-south Spanish Empire ended in Santa Fe and the younger, brasher

east-west American Empire reached no further than Independence, Missouri. A grand

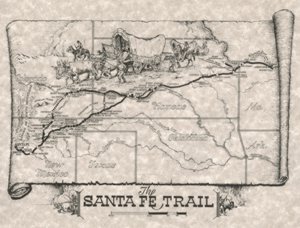

600-mile prairie lay in between, with mountains to pass and rivers to ford. Wagon

after wagon would follow the Santa Fe Trail, leaving a legacy of tracks that can

still be seen today.

The rumble of freight wagons, the shout of the bullwhacker, the snap of the whip,

the bellow of oxen, the quiet conversations in Spanish and English. These are

the trail sounds that evoke the pioneer spirit.

After all these years, the Santa Fe Trail still stirs the emotions. A flawless

sky of deep blue, as big as an A.B. Guthrie novel, above a prairie that seems

to roll forever. Caravans of commerce plodding westward to river crossings of

rushing torrents and dry washes. The choking, blinding dust and sudden chill of

the wind. The throaty thunder of approaching storms. The furtive glances for the

lurking presence of Pawnees and Comanches. The blare of bugles, the crack of rifle

fire, the endless brown seas of buffalo.

Today, the remnants of the trail await the traveler at scores of sites, great

and small, across five states and much of Northeast New Mexico's Union, Colfax,

Mora and San Miguel counties. Private landowners, nonprofit groups and federal,

state and local agencies manage most Trail resources. Look for the distinctive

signs that mark the auto tour that parallels the Trail.

How It All Started: When William Becknell left Old Franklin, Missouri, on September

1, 1821, heading west to trade with the Indians, he had little luck. But in New

Mexico he encountered some Spanish dragoons. Instead of taking him prisoner for

having entered Spanish Colonial Territory illegally, the soldiers urged him to

bring his goods to Santa Fe.

Becknell arrived there on November 16, quickly sold his wares and hurried back

to Missouri, his mules laden with silver coins. Mexico had declared its independence

from Spain, and American traders were now welcome in Santa Fe.

Within weeks, Becknell had organized another expedition. This time he took wagons

crammed with $3,000 worth of trade goods. His profit in Santa Fe was 2,000 percent.

The Santa Fe Trail was born, and a new era of prosperity began. For New Mexico,

the trail brought ever-increasing supplies of less expensive goods from the eastern

United States. As the caravans of commerce rolled west, they brought to New Mexico

not only new people, but a new language, skills and customs.

The trail at first led 909 miles through five states to Santa Fe, the capital

of New Mexico. As the American frontier crept westward, it became progressively

shorter.

Although the trail at first attracted adventurers and mountain men, its typical

travelers were businessmen. They financed hundreds of caravans of freight wagons

hauled by thousands of mules and oxen.

Often travel was just 12 to 15 miles a day. Yet merchants risked wagon accidents,

disease and Indian attacks. They weathered drought, storms and floods. After all,

there were profits to be made.

When the United States declared war against Mexico in 1846, U.S. troops took the

trail to declare New Mexico a United States Territory. In the following years,

as trade grew, several forts were built to protect trail traffic.

Trail trade flourished. In 1866, traffic peaked at 5,000 freight wagons. But the

railroad had reached eastern Kansas and as its tracks crept westward, trail traffic

dwindled. In 1879, when the first locomotive steamed into New Mexico, the Santa

Fe Trail was history. |

Click for Larger Version

|

|